Contemplative Noticing

A commitment we must make to ourselves when engaging this practice is a willingness to risk suspending the rush to action. The stance of Contemplative Noticing, 'taking a long, compassionate look at the real,' trusts that without this 'watchful suspension of action' we are doomed to sustain past patterns of interaction. The power of looking with a 'beginner's mind' creates the necessary openness and possibility of true freedom and mindful action.

When we embrace this level of Contemplative Dialogue, a humble commitment to seeing ‘what’s real here’ and a willingness to test assumptions begins to emerge. There is a willingness to dialogue with another to discover what I don’t know and an openness to different information

A commitment we must make to ourselves when engaging this practice is a willingness to risk suspending the rush to action. The stance of Contemplative Noticing, 'taking a long, compassionate look at the real,' trusts that without this 'watchful suspension of action' we are doomed to sustain past patterns of interaction. The power of looking with a 'beginner's mind' creates the necessary openness and possibility of true freedom and mindful action.

When we embrace this level of Contemplative Dialogue, a humble commitment to seeing ‘what’s real here’ and a willingness to test assumptions begins to emerge. There is a willingness to dialogue with another to discover what I don’t know and an openness to different information

The Ladder of Inference

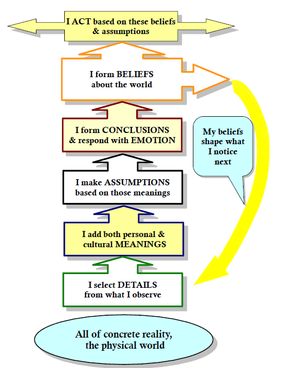

The Ladder of Inference is a model Chris Argyris developed for explaining how our minds quickly process information and make judgments. The Human brain takes in a flood of sensory information which it must filter and process every moment in order to function.

The ability to quickly interpret the sensory input from the world around us allowed our ancestors to learn and respond to their natural environment. The ability to quickly read a situation and make snap judgments which we inherited from our ancestors is a prized quality in managers and leaders. The fact that this process operates in a hidden fashion below our level of awareness gives it tremendous power for misuse through lack of conscious choices.

Based on a life-long sense that we experience the reality around us as it is and as we interpret it, we develop beliefs about the world that make perfect sense to us. The social construction of reality is the process by which people creatively shape their view of reality through social interaction. The way we interact with other people is shaped partly by our interactions with others, as well as by our life experiences. How we were raised and what we were raised to believe, how we perceived others, and how others perceived us, affect how we process and filter the world around us. Our perceptions of reality are colored by our beliefs and backgrounds.

Because people perceive reality differently based on their experience, they unconsciously decide how they are going to view a person or a situation, they act accordingly. Since we all perceive reality differently, our reactions differ. Our definition of a situation as good or bad, to be embraced or avoided, dictates our response to it which may differ from others with whom we’re engaged. This makes it increasingly difficult for use to agree on common starting points in our increasingly diverse and complex world.

Chris Argyris uses the image of a stepladder to represent the movement from concrete reality to increasing abstraction of the process that our Socially Constructed Reality takes to make meaning and sense of what we experience in daily life:

The discipline of noticing my own ladder of inference and openly working my way back down it helps me to be more directly in touch with what is real and essential in the world around me. Combining this with the ability to walk another person down their ladder of inference in a non-threatening way makes it possible to resolve a whole range of misunderstandings. Used proactively, this skill can be used to prevent many mistakes or mis-communications from taking place. Learning to be aware of our 'ladders of inference' gives us ways to understand one another much more effectively and accurately

The Ladder of Inference is a model Chris Argyris developed for explaining how our minds quickly process information and make judgments. The Human brain takes in a flood of sensory information which it must filter and process every moment in order to function.

The ability to quickly interpret the sensory input from the world around us allowed our ancestors to learn and respond to their natural environment. The ability to quickly read a situation and make snap judgments which we inherited from our ancestors is a prized quality in managers and leaders. The fact that this process operates in a hidden fashion below our level of awareness gives it tremendous power for misuse through lack of conscious choices.

Based on a life-long sense that we experience the reality around us as it is and as we interpret it, we develop beliefs about the world that make perfect sense to us. The social construction of reality is the process by which people creatively shape their view of reality through social interaction. The way we interact with other people is shaped partly by our interactions with others, as well as by our life experiences. How we were raised and what we were raised to believe, how we perceived others, and how others perceived us, affect how we process and filter the world around us. Our perceptions of reality are colored by our beliefs and backgrounds.

Because people perceive reality differently based on their experience, they unconsciously decide how they are going to view a person or a situation, they act accordingly. Since we all perceive reality differently, our reactions differ. Our definition of a situation as good or bad, to be embraced or avoided, dictates our response to it which may differ from others with whom we’re engaged. This makes it increasingly difficult for use to agree on common starting points in our increasingly diverse and complex world.

Chris Argyris uses the image of a stepladder to represent the movement from concrete reality to increasing abstraction of the process that our Socially Constructed Reality takes to make meaning and sense of what we experience in daily life:

- The base that the ladder stands on represents the concrete physical reality of the world and the events around us. From this ocean of data, we selectively notice or choose particular elements.

- We add cultural and personal meanings to what we have "noticed".

- We make assumptions based on ‘facts’ and the meanings we have assigned to them.

- Based on the assumptions we make we form conclusions about the particular situation and those involved in it.

- These conclusions become beliefs about the world around us.

- We make choices and take action based on these beliefs.

The discipline of noticing my own ladder of inference and openly working my way back down it helps me to be more directly in touch with what is real and essential in the world around me. Combining this with the ability to walk another person down their ladder of inference in a non-threatening way makes it possible to resolve a whole range of misunderstandings. Used proactively, this skill can be used to prevent many mistakes or mis-communications from taking place. Learning to be aware of our 'ladders of inference' gives us ways to understand one another much more effectively and accurately

Polarity Management

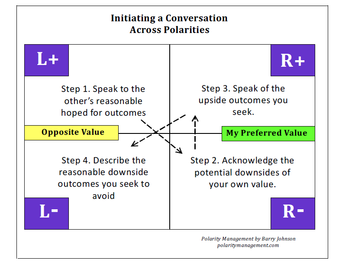

We often treat issues as either/or dilemmas. So too, we tend to frame potential solutions dualistically. That is, we often identify a ‘right’ solution and other ‘wrong’ solutions. Of course, the ‘right’ solution usually reflects our preferred position or values. When we attempt to address the situation, we insist that our preferred value is the all-purpose cure.

Barry Johnson suggests that what we miss is the fact that dynamic situations seldom reflect one ideal value or quality. More commonly, they reflect a range of values between which they fluctuate. He describes these dynamics as polarities, situations in which two values are dynamically related.

We recognize many common sense polarities in our everyday lives. Spending and saving represents a polarity most of us deal with on a daily basis. To excessively choose one or the other can lead us to bankruptcy or miserliness. Being aware that related values govern a dynamic creates the possibility of wisely managing the polarities rather than blindly insisting on one solution all the time. This is not unlike the thermostat in our home that regulates temperature by balancing heating and cooling to maintain a comfortable range.

When values are interrelated there is both a positive or upside to each pole (related value) and a downside or potential negative. For example, the traditional -- progressive polarity is common in a variety of settings. Each value has its potential positive outcomes, and each has a potential downside. Generally, the positive outcomes of the traditional position are: stability, clarity of roles and guiding values, builds on the inherited wisdom of the community. Likewise the positive outcomes of the progressive position are often: the ability to respond to new and changing realities; it includes those who may be new or traditionally excluded from the community; holds the possibility of growing beyond what the historic community was capable of.

Each position also has its potential downside. If the traditional stance were held to excess it could: be unable to adapt to changing conditions, reserve power for a select group, and develop a 'stick in the mud' irrelevance. The downside of the progressive position can be: an emphasis on change purely for the sake of change, discarding the inherited truth of the community and lapsing into relativism, creating instability that leads to organizational chaos.

We often treat issues as either/or dilemmas. So too, we tend to frame potential solutions dualistically. That is, we often identify a ‘right’ solution and other ‘wrong’ solutions. Of course, the ‘right’ solution usually reflects our preferred position or values. When we attempt to address the situation, we insist that our preferred value is the all-purpose cure.

Barry Johnson suggests that what we miss is the fact that dynamic situations seldom reflect one ideal value or quality. More commonly, they reflect a range of values between which they fluctuate. He describes these dynamics as polarities, situations in which two values are dynamically related.

We recognize many common sense polarities in our everyday lives. Spending and saving represents a polarity most of us deal with on a daily basis. To excessively choose one or the other can lead us to bankruptcy or miserliness. Being aware that related values govern a dynamic creates the possibility of wisely managing the polarities rather than blindly insisting on one solution all the time. This is not unlike the thermostat in our home that regulates temperature by balancing heating and cooling to maintain a comfortable range.

When values are interrelated there is both a positive or upside to each pole (related value) and a downside or potential negative. For example, the traditional -- progressive polarity is common in a variety of settings. Each value has its potential positive outcomes, and each has a potential downside. Generally, the positive outcomes of the traditional position are: stability, clarity of roles and guiding values, builds on the inherited wisdom of the community. Likewise the positive outcomes of the progressive position are often: the ability to respond to new and changing realities; it includes those who may be new or traditionally excluded from the community; holds the possibility of growing beyond what the historic community was capable of.

Each position also has its potential downside. If the traditional stance were held to excess it could: be unable to adapt to changing conditions, reserve power for a select group, and develop a 'stick in the mud' irrelevance. The downside of the progressive position can be: an emphasis on change purely for the sake of change, discarding the inherited truth of the community and lapsing into relativism, creating instability that leads to organizational chaos.

Single and Double Loop Learning

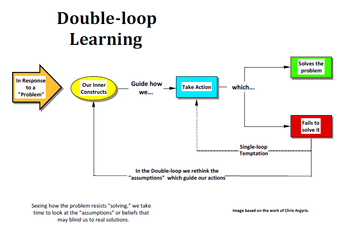

Single and double-loop learning refer to two different strategies for engaging problems in our lives. Single-loop learning is the simple strategy we use when something is broken. We fix it. If the light bulb is burned out in your reading lamp, you may first check to see if it is switched on, and check to make sure it is plugged in. The next thing you try may be to replace the light bulb with a new one. If the light begins working your problem is solved and you go on about your day.

We learned to solve problems this way as children. As adults, it's also a very effective way to solve many of the problems we find each day. If the car is almost out of gas, we stop at a gas station and refill the tank. We've just fixed a problem in a very simple way.

The problem with single-loop learning is that in some ways its simplicity and ease-of-use are addictive. The ability to be a problem solver is highly valued in our technical society. Corporate managers are brought in to solve major problems in a very short time span. It’s not a rarity that a CEO be dismissed after only a year or two for failing to generate a rise in stock price for his company. Yet, as problems become increasingly complex, the temptation of simple solutions enthusiastically applied inevitably creates more if not greater problems down the road.

One common practice that shows up in misapplied single-loop learning, is blaming. When an organization looks for a 'fall guy' to place the blame on, you can often be assured that a single-loop process is at work. Another common single-loop variation is used when an organization or group applies their preferred "solution" to every problem it faces. The dominant use of a 'preferred' or 'sanctioned' response is often rooted in values deeply ingrained in the organizational culture. While the value expressed maybe a very good one, applied in unreflective 'knee-jerk' fashion, it may cease to produce the quality results that the organization believes it will.

What makes double-loop learning different is the fact that instead of focusing purely on finding a solution to fix the problem, double-loop learning takes the extra step of reflecting on the possibility that my values or I may be unintentionally sustaining the problem. This is the genius of the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous; they draw attention away from outside circumstances and challenge the person to look at the ways that I am responsible and involved with the problem. Taking time for double-loop reflection may slow the initial rush to action, but creates the possibility of a lasting and effective response to a problem. In order to engage in double-loop learning, we first must notice the process responses we get caught in. Implicit in saying this is that we must be willing to look with a degree of humility and willingness to learn. In a group setting, it may require willingness and the skill to ask questions that momentarily slow a strong rush to action and conclusion.

Single and double-loop learning refer to two different strategies for engaging problems in our lives. Single-loop learning is the simple strategy we use when something is broken. We fix it. If the light bulb is burned out in your reading lamp, you may first check to see if it is switched on, and check to make sure it is plugged in. The next thing you try may be to replace the light bulb with a new one. If the light begins working your problem is solved and you go on about your day.

We learned to solve problems this way as children. As adults, it's also a very effective way to solve many of the problems we find each day. If the car is almost out of gas, we stop at a gas station and refill the tank. We've just fixed a problem in a very simple way.

The problem with single-loop learning is that in some ways its simplicity and ease-of-use are addictive. The ability to be a problem solver is highly valued in our technical society. Corporate managers are brought in to solve major problems in a very short time span. It’s not a rarity that a CEO be dismissed after only a year or two for failing to generate a rise in stock price for his company. Yet, as problems become increasingly complex, the temptation of simple solutions enthusiastically applied inevitably creates more if not greater problems down the road.

One common practice that shows up in misapplied single-loop learning, is blaming. When an organization looks for a 'fall guy' to place the blame on, you can often be assured that a single-loop process is at work. Another common single-loop variation is used when an organization or group applies their preferred "solution" to every problem it faces. The dominant use of a 'preferred' or 'sanctioned' response is often rooted in values deeply ingrained in the organizational culture. While the value expressed maybe a very good one, applied in unreflective 'knee-jerk' fashion, it may cease to produce the quality results that the organization believes it will.

What makes double-loop learning different is the fact that instead of focusing purely on finding a solution to fix the problem, double-loop learning takes the extra step of reflecting on the possibility that my values or I may be unintentionally sustaining the problem. This is the genius of the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous; they draw attention away from outside circumstances and challenge the person to look at the ways that I am responsible and involved with the problem. Taking time for double-loop reflection may slow the initial rush to action, but creates the possibility of a lasting and effective response to a problem. In order to engage in double-loop learning, we first must notice the process responses we get caught in. Implicit in saying this is that we must be willing to look with a degree of humility and willingness to learn. In a group setting, it may require willingness and the skill to ask questions that momentarily slow a strong rush to action and conclusion.